picture: Wilhelm Gunkel on unsplash

We interviewed the authors of the guidelines „From (ecodesign) idea to market“ – Anke Skopec and Kristin Dorl - about their experiences with (green) innovation, new business models and their economic feasibility.

Dear Ms Skopec, dear Ms Dorl - could you please introduce yourselves briefly to our readers?

Anke Skopec:

Yes, with pleasure. I am Anke Skopec, one of the founders of the Berlin Institute for Innovation Research (BIFI) eleven years ago. My professional background is a degree in psychology and a degree in economics. I specialised in social psychology, focusing on the psychology of experience and behaviour under the influence of social factors - in other words, how people interact with each other. I wrote my dissertation on the optimisation of corporate processes. This gives me the know-how to competently conduct research studies in my current professional field, where I examine the economic viability of new business models.

Kristin Dorl:

My name is Kristin Dorl. I have been at BIFI for about six years now. I studied international information management, with business administration and psychology as important subjects. After that I gained experience in start-ups, also internationally. For example, I lived in Africa for four years and helped to build a German start-up there.

How did you come to found an institute for innovation research?

Anke Skopec:

Five of us founded BIFI together; four of the founders had met in their former jobs at a traditional market research agency. There we noticed that market research has entrenched structures which allow the management team of a medium-sized or larger company to come up with a new idea that they want to push through themselves. Then all they really need are figures to confirm the idea. In that case, it's already quite clear at the beginning what the final result has to be.

We said to ourselves: it can't work like that. We need market research to seriously shape better products and better companies. It has to recognize and address the unpalatable truths. This is a risk we have to take, because only then can the company gain the added value of making the right decisions based on empirical knowledge. That was the impetus for our own institute, which works closely with research and science. And that’s still the case - even after eleven years!

You both also studied psychology and economics, among other things. What role does psychology play in innovation research?

Anke Skopec:

In the classic market research context, it is the economists who have a lot to say. In our case - the testing of disruptive innovations - future consumers cannot simply be asked what they would do, because they don't know! They have not had any experience with the product because it is not yet on the market. This is where the psychological skill of hypothetically representing a "future" and predicting behaviours through more complex questioning techniques and experiments has an advantage, despite being much more difficult than classic market research on existing products. That is why we use the term “innovation research".

In the context of sustainability, behavioural change plays a big role. How do you approach that? Where do you start?

Anke Skopec:

Our approach to behavioural change is twofold: Will consumers change their behaviour? We do not intervene in a manipulative way. If new products and services actually meet an existing need, the product can become successful. That means we don't want to help determine whether the biscuit package should be red or blue so that more people will buy it, rather we want to make the biscuit better and find out how the biscuit should taste. That's why we don't try to change the behaviour of consumers, but rely on swarm intelligence to optimise the conditions.

Our approach is that consumers cannot tell us individually how they will behave in the future. That's why we as researchers are needed to do this translation work. Also the other way around, such as: Dear company, please change the way you design your product and address people, because with the knowledge of what they really need, you can optimise your product in the right direction.

That’s been our practical experience so far, that the companies' eyes are opened to which product characteristics actually matter to the consumers and which don’t. We call this a driver analysis: which product characteristic drives the success of the business model? Often, these factors aren’t what you would expect.

Feedback Factory | © BIFI Institute Berlin

Feedback Factory | © BIFI Institute Berlin

Do you think that the topic of sustainability has become more important over the years?

Anke Skopec:

Definitely. That's what 100 per cent of our analyses show! The topic has permeated every stratum of the population. More and more consumers say that sustainability is an issue for them. Companies now rely on sustainability, incorporating it as a major pillar in their products and services to meet a much larger, more conscientious market of consumers.

What does the growing number of green innovations mean for your institute?

Anke Skopec:

The number of enquiries from companies with a sustainable idea is very high and continues to rise. In my opinion, this is mainly due to the fact that start-ups, e.g. in the food sector, nowadays really have to believe in their own product and develop the best product they can imagine. Otherwise, the product wouldn’t be competitive since there is already such a huge range in the food sector.

We recently had the case of a young man who wanted to launch his grandma's Korean special sauce because it was a delicious secret family recipe. He decided one day: this sauce needs to be shared with the world! But there are already plenty of Korean sauces. So what can you write on it that doesn't just say, "I think my grandma's sauce is the best." Of course, in the long run, the taste will prevail if the quality is right. But first, attention has to be drawn to it.

We recently had the case of a young man who wanted to launch his grandma's Korean special sauce because it was a delicious secret family recipe. He decided one day: this sauce needs to be shared with the world! But there are already plenty of Korean sauces. So what can you write on it that doesn't just say, "I think my grandma's sauce is the best." Of course, in the long run, the taste will prevail if the quality is right. But first, attention has to be drawn to it.

By now, all start-ups in the food sector have realised that they have to include sustainability as a feature, to ensure uptake from the more conscientious consumer, otherwise these new products have almost no chance of success. They are too expensive and aren’t ready for mass production. The founders usually only have 5,000 or 10,000 euros in their pockets. Then they put 2,000 euros into the production of 1,000 sauce bottles to bring to market. They can only make their next move once they are sold and they’ve got their money back.

In such cases, the consumers need to think: "It's okay if I pay 3-4 euros for the sauce". This price is justified because all the ingredients are sustainable and that adds value. Companies often attach a lot of importance to the fact that not only the ingredients, but also the process steps are carried out sustainably, simply from the conviction: "I am now entering the market with a product that will be the best in the world".

Kristin Dorl:

We find this in the digital sphere as well as the material sphere, such as in food retailing, where there is a strong focus on the provenance of individual components. Services and digital products are also incorporating more sustainable aspects. In our studies and in exchanges with our customers, the value that consumers perceive with regard to sustainability in digital products is becoming an increasingly important topic. How can value be added by integrating sustainability aspects with digital business models as well? To what extent is it important for both consumers and companies? For digital services that involve logistics, the stereotypical issue is that the delivery has an environmental impact in one way or another. Companies are aware of this and also look to offset and deal with it themselves.

Usability Interview | © BIFI Institute Berlin

What do you think is the most common cause for "green" innovations to fail?

Anke Skopec:

That's a very good question – not because the innovation is "green", but simply because starting a new business involves a lot of risks. In this respect, I can only answer this question in terms of start-ups’ most common pitfall: the composition of the team and teamwork. We all know too well from lockdown that working from home requires much more self-discipline. This is also the case in the start-up sector where you don't have a boss, but can do as you like.

The team constellation has to be right. The relevant competences must be present at a professional level. You have to be able to achieve more with fewer opportunities and in less time than others.

Meanwhile, almost half of the business models that come to us have something "green" to offer. Often there are situations where the price-performance ratio is not right:

We recently tested a device that recaptures and recycles waste water internally. This is particularly relevant for countries in which there is a greater scarcity of water. However, the purchase costs for such a device are relatively high - you first need the money to treat water at home. That's one thing people here wouldn't consider yet: short-term cost-benefit factors are carefully considered in Germany. Consumers still want minimal effort and maximum comfort. Some sustainability concepts have not yet made this leap. Cost savings are rarely the goal of sustainable prototypes.

We recently tested a device that recaptures and recycles waste water internally. This is particularly relevant for countries in which there is a greater scarcity of water. However, the purchase costs for such a device are relatively high - you first need the money to treat water at home. That's one thing people here wouldn't consider yet: short-term cost-benefit factors are carefully considered in Germany. Consumers still want minimal effort and maximum comfort. Some sustainability concepts have not yet made this leap. Cost savings are rarely the goal of sustainable prototypes.

In the end, consumers look at their own wallets before complex global issues like climate change.

Kristin Dorl:

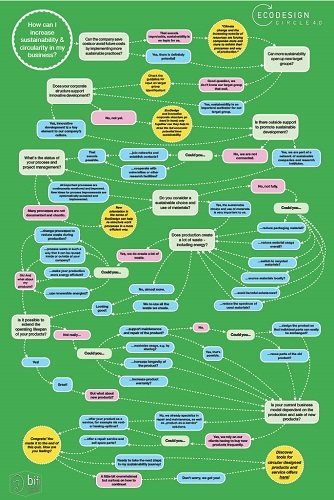

The failure of sustainable ideas or activities is something that always depends on the individual case and a number of other factors. In the field of sustainability, it also depends on basic economic considerations. Green innovations often are fundamentally driven by a motivation to be sustainable, which means that I want to develop a sustainable product purely for the sustainable aspect. But you can’t ignore economics, i.e. you have to jump through the economic hoops: Is the target group large enough? What additional costs, if any, will be incurred if I switch my production to more sustainable variants? On the other hand, what resources can I save? What will this cost structure change for me? And finally: do all these considerations come together in a holistic model that is also economically sustainable?

Anke Skopec:

An innovation is an invention that has become established on the market. That means if something is new but no one needs it or you can't convey why it adds value, it's not an innovation. It's the same with sustainability - there is ecological sustainability, social sustainability and economic sustainability: is this product future-proof?

I think it is extremely important nowadays to look at sustainability as a holistic concept of these three components.

Decision Circle | © BIFI Institute Berlin

Decision Circle | © BIFI Institute Berlin

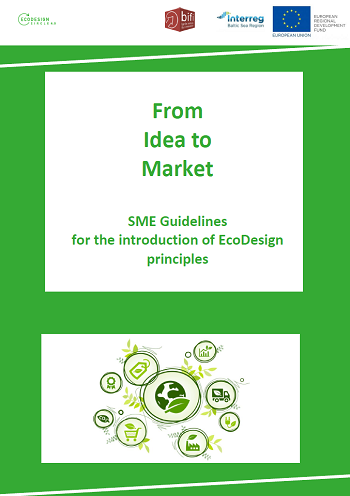

This also brings us to the guide you just finished: From (Ecodesign) Idea to Market. How did you approach the guide? What was important in your point of view, what kind of assistance does it offer?

Anke Skopec:

We have gathered a lot of insights from our research, i.e. from the empirical research studies: What works and what doesn’t? What can go wrong and why? Where should we look more closely? Where are there opportunities? Our work also has an advisory component, in that we listen to what the problem is beforehand: What is the real problem? When clients request a questionnaire for a survey, for example, we first talk to them and ask: "What exactly is the problem? What strategic question needs answering in your company? What is the core issue that you need to work on in order to optimise something?" This often reveals that it is perhaps not a questionnaire that addresses the challenges, but a more profound question that requires a completely different method. In the end, we know exactly which questions are important to the company and what the answers should achieve. That’s why we then give very concrete recommendations for action: What does the company have to do now?

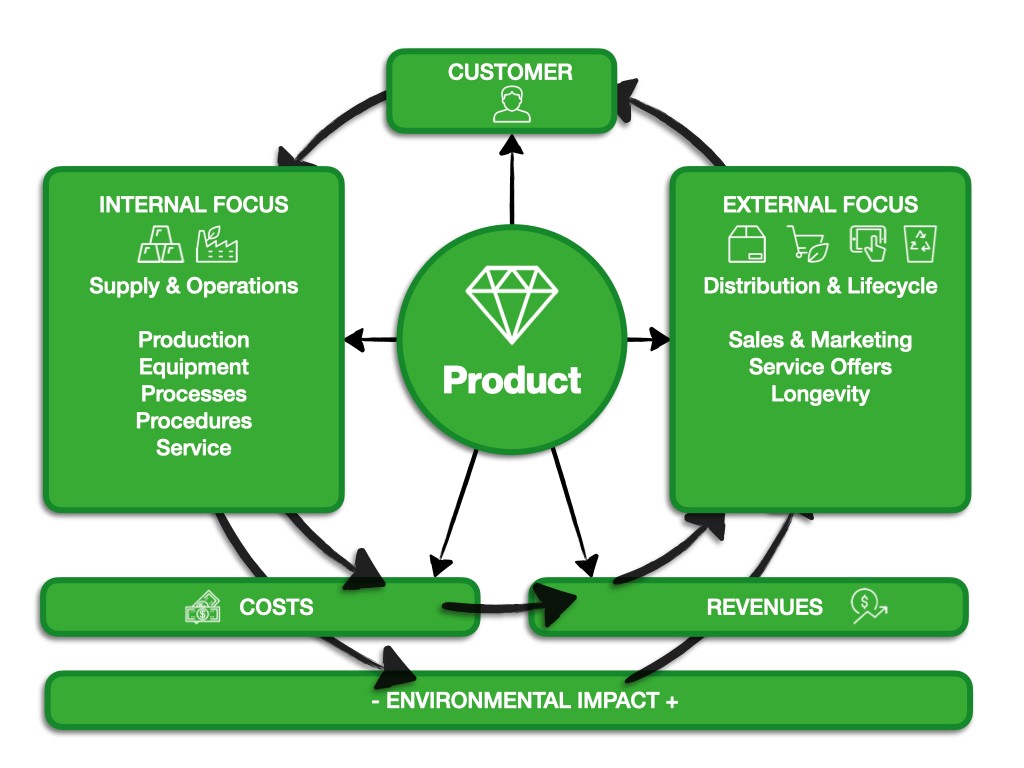

This gave us a lot of insights into these companies, their problems and needs, which we combined and structured in the guide: What can be done in which phase? Then we applied the methodological structure: Which research topics can be broken down? Where can a company start? Based on this, we made the circular model and identified related components.

Kristin Dorl:

We soon agreed that the perception of an offer is essential – whether it is a specific product, a service or even a mix of product and service. The offer is viewed against different backgrounds, all related to each other. Questions such as: What is my target group like? What do my internal processes look like? What do my external processes look like? What is the cost structure, the turnover structure and what environmental impact do these activities have? What environmental impact do my internal processes have? How can I reduce this and thereby save resources? How can I tap into new markets with my product ideas? How can I make savings through marketing or service changes?

All these questions are very much interrelated and provide a holistic picture. I can start at different points when looking at my offer, but of course I can also look holistically at how product changes or service changes affect my entire business.

Focus Group Discussion | © BIFI Institute Berlin

Focus Group Discussion | © BIFI Institute Berlin

What would you change, or what leverage would you put in place to make it easier for sustainable innovations to get on the market and hold their own?

Anke Skopec:

We are faced with the problem that we have a great deal of information opacity, which leads to market power. And this market power lies with the old, slow, very big, very rich companies. That makes it harder for new, smart business ideas.

![]() For example: If a new start-up lemonade wants to get into a big supermarket chain, it needs a deposit of up to 50,000 euros, because the supermarket doesn't know if this lemonade will ever be bought. The money is a kind of marketing fee, e.g. for display stands, etc. The start-up pays all the money itself. I talked about budgets earlier and you can imagine how far away that is from the start-ups' possibilities.

For example: If a new start-up lemonade wants to get into a big supermarket chain, it needs a deposit of up to 50,000 euros, because the supermarket doesn't know if this lemonade will ever be bought. The money is a kind of marketing fee, e.g. for display stands, etc. The start-up pays all the money itself. I talked about budgets earlier and you can imagine how far away that is from the start-ups' possibilities. We have also tried to tackle the problem of market opacity ourselves. We opened a test department store, where we offered start-up products that were not yet represented in the nationwide trade. We then spent half a year collecting what consumers said, how they reacted, what they bought and what they touched. The consumers were allowed to try out everything for free. Then, with the help of small feedback cards, they were allowed to tell the start-up what could perhaps be improved or what they liked, whether they would buy the lemonade or give it to someone as a gift, whether they already know it or perhaps find it completely awful. All this data we collected was then evaluated. With their independent evaluation report, the startups could go to a big supermarket chain and say, "My product did so and so... You can decide whether you want it, otherwise I'll go to another supermarket because they need my innovation, too." The supermarket chains use their market power to leave the risk with the small producers. But it is actually their job to take that risk, because they are also looking for innovative, new products, because consumers are looking for innovative, new and, above all, sustainable products. And with this empirical market data, the market power has actually shifted. The ten best products from the test department stores' range were able to choose their retail partners themselves.

We have also tried to tackle the problem of market opacity ourselves. We opened a test department store, where we offered start-up products that were not yet represented in the nationwide trade. We then spent half a year collecting what consumers said, how they reacted, what they bought and what they touched. The consumers were allowed to try out everything for free. Then, with the help of small feedback cards, they were allowed to tell the start-up what could perhaps be improved or what they liked, whether they would buy the lemonade or give it to someone as a gift, whether they already know it or perhaps find it completely awful. All this data we collected was then evaluated. With their independent evaluation report, the startups could go to a big supermarket chain and say, "My product did so and so... You can decide whether you want it, otherwise I'll go to another supermarket because they need my innovation, too." The supermarket chains use their market power to leave the risk with the small producers. But it is actually their job to take that risk, because they are also looking for innovative, new products, because consumers are looking for innovative, new and, above all, sustainable products. And with this empirical market data, the market power has actually shifted. The ten best products from the test department stores' range were able to choose their retail partners themselves.

That’s still an issue for me, even in a large context. We tried to change and adapt with a small, local measures. There were levers and they worked, but in the big picture, I would want to change this overwhelming market power. Consumers need much more transparency about what they are actually buying, what is sustainable or what health effects products have.

Kristin Dorl:

I think we are definitely going in the right direction with the support opportunities offered by the EcoDesign Circle project: to create networks and support opportunities for companies; obtain advice; exchange ideas with each other; strengthen motivation; even join forces to counteract huge market powerhouses. We have many companies and enterprises with great ideas that are innovative, with the drive to implement them ... With further support we can maintain the momentum to continue in this direction, both in the process of ecodesign and also in the implementation phase.

Interview: Lisa Marie Fiebig and Conrad Dorer

picture: Wilhelm Gunkel on unsplash